On Wednesday 5th May 2021, the inaugural session of our new research series, Remix Studies Conversations, took place via Zoom, facilitated by the ADRI, Penn State University. The event was organised by Eduardo Navas, xtine burrough and myself to coincide with the launch of our latest book on remix, The Routledge Handbook of Remix Studies and Digital Humanities, which was published earlier this year. The session was well attended and featured presentations from four of our contributors from this book and previous anthologies, Anne Burdick, David J. Gunkel, Paul D. Miller, and Virginia Kuhn.

Top (R-L): Eduardo Navas, Owen Gallagher, xtine burrough; Middle (R-L): Anne Burdick, David J. Gunkel; Bottom (R-L): Paul D. Miller a.k.a. DJ Spooky, Virginia Kuhn

Eduardo hosted and introduced the guest presentations, which were followed by a lively discussion and q&a session. It was an absolute pleasure to be part of such an invigorating event and to hear our colleagues speak so passionately about remix. There were so many more questions we could have asked and tangents to explore, but the 2 hours flew by, and judging by the messages we received, the event was enjoyed by our participants too, remix enthusiasts and digital humanities scholars alike. One of the most amazing things for me was to see and hear our contributors present their work live and in-person – I felt it really brought their ideas to life in a visceral way that printed text simply cannot. We have spent the past 3 years editing and rewriting the Handbook, going back and forth with almost 40 contributors, reading, re-reading, editing, suggesting, re-writing and doing this process multiple times for each chapter, but hearing Anne, David, Paul, and Virginia talk about their work so passionately in person was a truly memorable experience for me. It felt like we were all at a real conference, except it was far more efficient using Zoom! Participants could ask questions via chat during each session and speakers could respond in real-time, ahead of the allocated q&a sessions. The only thing that was missing was being able to go for a drink with everyone and elaborate further into the wee hours of the morning over a few glasses of wine or whiskey. For now, these virtual sessions are an excellent alternative, but I look forward to meeting our contributors IRL at some point in the hopefully not too distant future.

For me, this book, and this research series are about bringing remix scholars/practitioners and digital humanities scholars together – to create a space were cross collaboration can occur and ideas can be shared, borrowed, combined and remixed. There are so many practical applications of remix to be utilised in the digital humanities, as evidenced by many such examples contained in the chapters of our book, and likewise, remix studies, as an emerging academic discipline can benefit greatly from the influence of digital humanities scholarship.

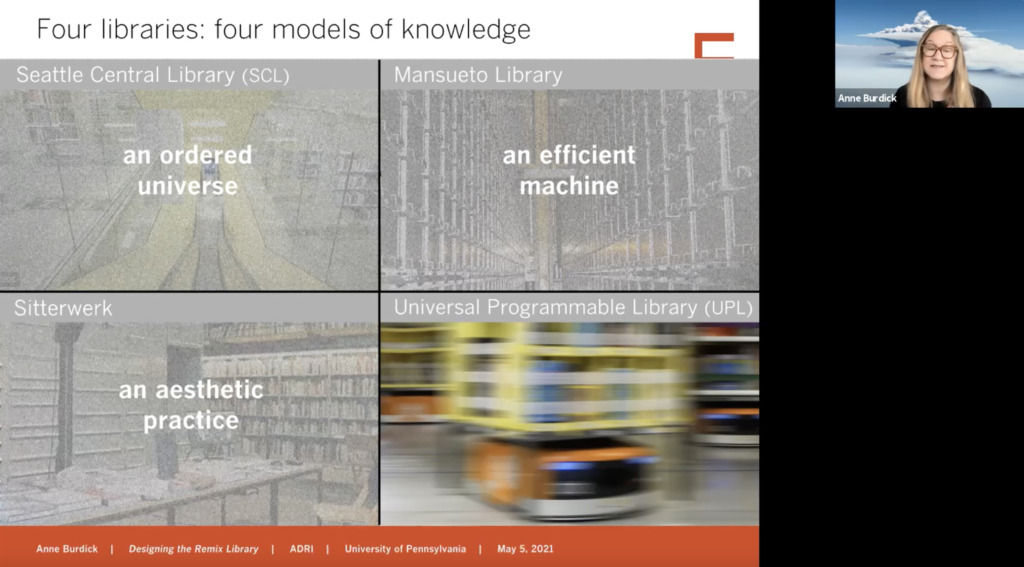

The session kicked off with a brief introduction by Eduardo, myself and, xtine, and then Anne Burdick took centre-stage, with her talk on “Designing the Remix Library“, also the subject of her chapter in the Handbook. She discussed four libraries in particular, the Seattle Central library (which we remixed for the cover of our book), the Mansuetto library, Sitterwerk, and the theoretical Universal Programmable Library. For Anne, SCL’s architecture and operations reflect an ordered universe, Mansuetto, an efficient machine, Sitterwerk – aesthetic practice, and the UPL, a perpetual state of becoming, or what Eduardo refers to in his work as a regenerative remix.

Anne Burdick – “Designing the Remix Library”

A thought occurred to me while Anne was presenting, that all of the examples she discussed are physical libraries in the real world (with the exception of the UPL – but it is a model for a hypothetical physical library). Given that my recent research on remix is concerned with the role of virtual environments and video games in the digital humanities (my chapter in the book investigates this topic), I was curious whether Anne has considered the possibility and potential of virtual library spaces? That is, could networked, social, virtual libraries (actual virtual spaces one can move around in via VR or through a video game-style platform) take the place of physical library buildings, which have been waning for years?

In my home country of Ireland, the role of physical libraries has shifted more towards becoming like glorified Internet Cafes for the socially and economically-challenged, rather than sites of silent, contemplative reading and learning for all members of the community. I have been passionate about libraries for most of my life – some of my earliest childhood memories are of checking out books at our local library in Dolphin’s Barn, Dublin – I can still see and smell the books and the little green tickets that were placed inside the sleeve inserted into the front matter of the book, and stamped with the date when the book had to be returned. I also much prefer reading physical printed books than ebooks – although I occasionally use an iPad for reading, I would take the printed page any day of the week. But still, I am fascinated by the potential of recreating the experience of a physical library in virtual reality. Bringing all of the benefits and feelings of a quiet place to study into the virtual environment, with the added benefits of networked digitality and social exchange that can occur within virtual spaces. Once VR becomes more normalised, I think this will be a natural next step for the library, as we have already seen similar shifts occurring in the visual realm of art galleries and museums.

David J. Gunkel – Computational Creativity, Algorithms, Art and Artistry

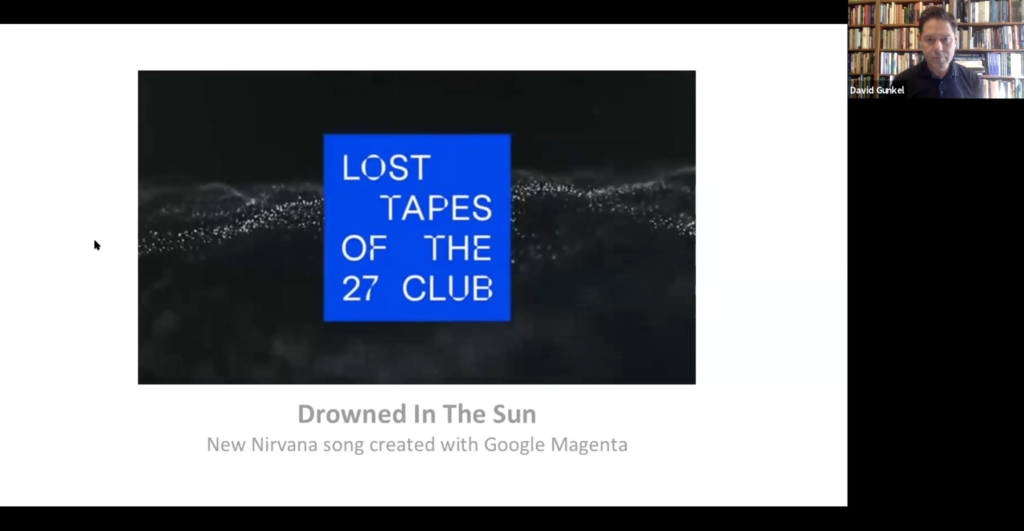

Next up, David J. Gunkel presented a fascinating talk on “Computational Creativity, Algorithms, Art and Artistry“, again, directly related to his chapter in the Handbook. David argues that computational creativity remixes remix as the art of posthumanism. His talk was concerned with the relationship between AI, machine-learning applications that produce various forms of creative output, such as music, art, and literature, and the (possibly diminishing) role of the human in this creative process. He led with a contentious example of a “new” Nirvana song called “Drowned in the Sun“, created using Google Magenta’s AI neural network, which analysed all of Nirvana’s back catalogue for musical style, and chords and lyrics for songwriting elements ultimately leading to what I would consider to be a “musical deepfake” of a Nirvana song. It sounds similar to many of Nirvana’s previous songs, and the singer sounds like Cobain, so to an untrained ear, one would be forgiven for thinking it could be an unreleased Nirvana demo, but it was in many senses created/produced by a machine.

However, the debate became more interesting and muddied once David revealed that the various iterations spit out by Google Magenta as midi files were “evaluated by human curators”, and the melody and lyrics of the song were recorded in a traditional manner by a human Kurt Cobain soundalike singer. David alluded to the process of remix as outlined by Kirby Ferguson in his documentary, Everything is a Remix – “copy – transform – combine”, which this Nirvana “remix” arguably follows. For David, remix is a tool used by human artists, and the question is, can computational creativity exist without humans to hear, see and evaluate it? Could machines create art purely for other machines? To me, as a Nirvana fan, at first listen, the Nirvana deepfake “Drowned in the Sun” does not sound artistically “good” to my ear. Obviously, this is a highly subjective reaction and the question of what makes art good is far beyond the scope of this topic, but I wonder what the remaining members of Nirvana think about it? And how would Cobain himself feel about this track if he were still with us? And what about the legions of Nirvana fans beyond myself – would any of them embrace and love this as an unexpected addition to the Nirvana catalogue? I would love to see a survey designed to measure this. The results could be quite interesting. The whole area of deepfakes is directly related to this topic, and NFTs were also touched upon by Paul Miller during the Q&A, but one thing that was not mentioned at all, is copyright. This Nirvana deepfake, which is being openly declared as such, does not directly sample from any Nirvana recordings, or lyrics, yet it captures the “feel”, “sound” and “essence” of a Nirvana song. Where does this fall on the spectrum of copyright and fair use? A question for another day.

Paul D. Miller, a.k.a. DJ Spooky presented next, commenting on the previous speakers contributions and alluding to his own ongoing remix work and its relationship to current global developments. One comment I loved was the idea of the remixer as being like Anansi, the “Trickster”, originating from West African and Caribbean folklore. I have often thought that tricksterism, or “mischief” is a core theme that runs through so much remix work, from the Yes Men, to culture jamming, to my own critical remix videos. The act of repurposing words, images, sounds, and videos without permission is inherently mischievous. I also think Anansi is a fitting metaphor for the remixer, as he is a spider, with multiple legs/arms enabling him to do several different things simultaneously, and uses his cunning, creativity and wit to overcome adversaries. Paul also mentioned the recent Gamestop fiasco that occurred on Wall Street in recent months, where, as Paul says “kids were remixing stocks” – stocks became memes and trading became a mischievous act – so-called meme “stonks” like Gamestop, AMC, and Blackberry, were traded en-masse by new money online day-traders through platforms and apps like Robinhood, which artificially inflated the value of these stocks, causing old money Wall Street hedge funds to lose billions of dollars and some lucky individual traders to become millionaires overnight. It was a fascinating experiment in a kind of coordinated online activism, but for the purposes of Paul’s talk, I had not heard it being referred to in relation to remix before and I think this is a very astute observation.

Paul has himself famously remixed D.W. Griffith’s racist KKK film, “The Birth of a Nation” (1915) into his own version entitled, “Rebirth of a Nation“, which has been screened all over the world. As Paul was talking about this, I was fascinated to find out what Paul thinks of the current “cancel culture.” Given that Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” is an openly racist film, controversial and condemned in many circles, it seems like it would be a prime candidate to be fully “cancelled”, – “erased from existence”, removed from acceptable cultural memory. However, this would be a travesty. As all film scholars know, D.W. Griffith was almost single-handedly responsible for developing the early “language of film”, particular in terms of shot types, camera angles, and continuity editing, that informed almost every film that came out of Hollywood over the past century. It’s importance in the history and development of cinema cannot be understated. Yet, it is openly racist.

In the more recent past, “cancel culture”, i.e. pressure from sensitive consumers, has led to studios and media conglomerates like Disney, HBO and the BBC restricting, re-editing, or simply removing content from their platforms because they contain “negative depictions” of minority groups, for example. Disney’s “Dumbo” and “Peter Pan” were slammed for racist depictions, HBO removed “Gone with the Wind” from HBO Max, and the BBC removed particularly offensive episodes of Little Britain and Fawlty Towers from the BBC iPlayer. As a staunch defender of freedom of expression, I find these acts cowardly and reprehensible for the same reason that I do not believe “Birth of a Nation” should be deleted from history. We can all learn from the mistakes of the past without pretending it didn’t happen. Paul also recommended a 2020 documentary film “Coded Bias“, which is an exploration into the fallout of MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini’s discovery of racial bias in facial recognition algorithms. Referring back to David’s talk in relation to “remixing the algorithm”, Paul also mentioned the example of Japan’s Hatsune Miku, a completely virtual pop star developed by corporations to help sell Toyota cars, but she took on a life of her own and has packed thousands of fans into stadiums for “live” concerts. Her voice is computer-generated and her image is essentially an anime-style animation. Is this the future of music?

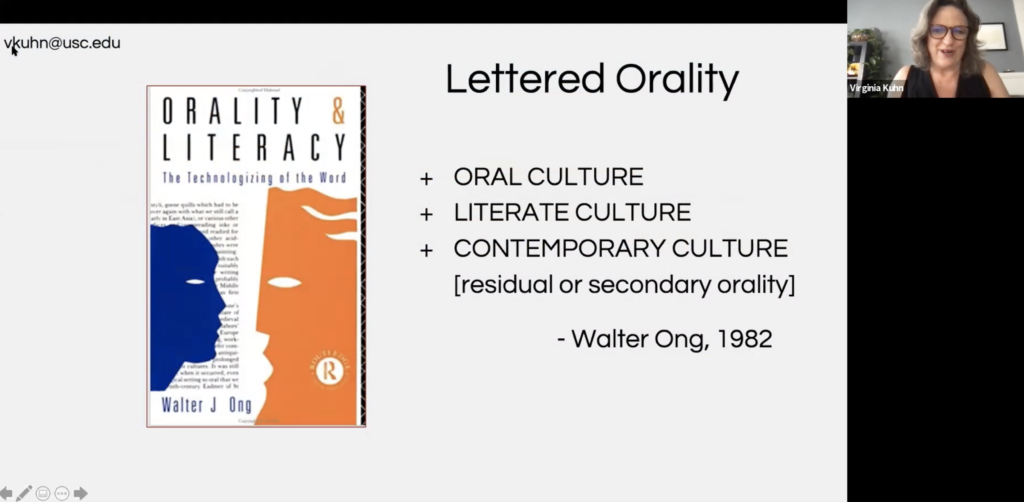

Virginia Kuhn – Remix and Lettered Aurality

Finally, Virginia Kuhn presented her talk on “Remix and Lettered Orality“, referring to the idea that “lettered orality” has often been considered an oxymoron in a similar way to “media literacy”, yet Virginia sees the value of both terms in relation to remix. Virginia’s talk, and her chapter in the Handbook dealt with the cultural artefact known as the “video essay”, which she has been teaching and helping students produce for more than a decade. Virginia highlighted the importance of words, which are often relegated to second, third or even fourth place in video content, (if they are included at all) after moving images, still images, and sound. I quite agree with Virginia on this point, and I also teach motion or kinetic typography to my students for inclusion in remix videos. Seeing particular keywords on screen as they are said, or in reference to a visual that appears can be an extremely impactful way to reinforce an idea or concept in the mind of the viewer. It’s almost like a form of subliminal programming, but often the act of including actual written words on screen as a core part of a video is neglected. In terms of remix, and especially sampling, words occupy a unique place compared to other media types. Sampling an image or video clip, for example, is visually undeniable – we can see the sampled image on screen. Likewise with music, we can hear a sampled audio snippet in a new musical mashup. However, sometimes, DJs and remixers might re-record a musical riff rather than directly sample it, as occurred with the famous bass line from Chic’s “Good Times” in The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” which muddies the waters somewhat.

When it comes to words, as Virginia mentioned, we don’t tend to think of words in the same way as we think of images or sounds, as fixed media components. We are so used to copying and pasting text from Microsoft Word or from websites into new documents that we don’t consider pasting it in the same font and at the same size that it originally appeared, for example. This is an aspect of text and words that I am quite interested in and would love to explore further in the future, i.e. directly sampling words as they appear on pages in a book is truly sampling text, as opposed to copying and pasting and changing the positioning, font etc. Virginia memorably stated that “print changes consciousness”, a fascinating concept, and during her talk, she recommended a documentary, the Quantum Activist, in which Dr. Amit Goswami challenges traditional views of existence and reality – I look forward to watching it. For Virginia, remix video essays use all of the available semiotic resources – words, images, moving images, sounds, and some kind of argument. The questions I wrote down for Virginia were in relation to her perception of the power of video essays, i.e. their persuasive power and potential to influence many viewers over time, and potentially instigate real, measurable social or political change, in a similar way to how propaganda material has done in the past. Virginia’s chapter in the Handbook describes how she worked with a number of other scholars to produce a series of collaboratively remixed video essays using the online platform, Scalar – a fascinating insight into the process of video essay creation, which may be of interest and benefit to many digital humanities scholars.

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed this session with Anne, David, Paul, Virginia, and I’m already looking forward to the next one, which Eduardo, myself and xtine are hoping to organise during the summer, followed by several more in the Autumm/Fall. Thanks also to our participants and other contributors who will definitely be featuring in our future sessions.

The full Zoom session can be viewed via ADRI’s Zoom page here.

An audio recording (for podcast listening) is available here, and the text-chat transcript, here.